#5: Data is an asset

But are you treating it like one?

A few articles back I introduced 5 principles behind the business of data.

I’ve already discussed the first principle - connecting data to your business.

In case you missed that, here’s the link…

This week, let’s move to another principle - treating data as an asset.

We often talk about data being an asset, but do we really know what this means?

(There is a lot of research on this theme, some of which I’ve used, so for the benefit of my more studious readers, I’ve included links to sources throughout 📚).

Do you think data is important?

Over the course of 18 months, I asked upwards of 500 business leaders this stupendously simple question.

At the time I was developing data strategies for a variety of organisations, including major charities, TV channels, financial services businesses, and government bodies.

This question was an icebreaker, as I settled an executive audience into a review of how well (or not as the case may be), their business was doing data-wise.

There are no prizes for guessing that almost everyone I interviewed agreed data is very important and had some pretty good reasons for believing this.

However, once lulled into thinking their interviewer was a simpleton, I then asked this zinger:

✨ “So, does this mean your organisation treats data as an asset?” ✨

A literal asset. Something that has significant measurable value, which is protected, managed, and exploited relative to that value.

In other words, like any other business asset.

This follow-up question was often a stumper. After some pondering and chin scratching, many sighed and shook their heads.

Cue a long list of data problems, as my interviewees vented:

😔 “My data is completely inaccurate and I don’t trust it.”

🤹♀️“We’ve got four different versions of the same data, and I don’t know which is right.”

🕰️ “The data is out-of-date by the time it reaches me.”

😵💫 “There is no context to the data, so even where I have it I can’t understand it.”

Or my all time favourite:

💩 “It is utter shite. So, I don’t use it.”

While most people thought of data as an asset, a litany of challenges were evidence that it wasn’t being treated as such.

Here’s the problem. When most of us say ‘data is an asset’ we’re using the term loosely. It often reflects a desire or hope that it is important, beneficial, and something we should care about.

It doesn’t mean it is being formally treated like any other asset.

I’m not having a pop at these 500 business executives. The reason I frame data in this way, is if anyone is going to understand the implications of treating something as a literal asset, it is these folks.

(When the ‘data asset penny’ drops at the top of an organisation, we start to see real change in the way data is treated. So there is method to my madness).

Few of us are taught that data is a literal asset. It’s not something covered by most business courses, and the accounting profession has been notoriously wary of it.

Ironically, true asset thinking has eluded many data professionals as well.

Let’s start with the basics

What is an asset?

Investopedia defines it as:

“A resource with economic value that an individual, corporation or country owns or controls with the expectation that it will provide future benefit.”

There are some operative words here:

A resource

Economic value

Owned

Controlled

Expectation of benefit

At the organisation level, you’re probably used to seeing two types of asset on the balance sheet - tangible assets and intangible assets.

Tangible assets are physical material resources, such as cash, buildings, land and machinery (you can touch them, and they are valuable).

Intangible assets are resources without material substance, but with definable value. Such as intellectual property, trade secrets, brand, and goodwill (you can’t touch them, but that doesn’t mean they’re not valuable).

Data as an intangible asset

This is the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) definition of an intangible asset.

It is hard to argue that data doesn't meet these conditions:

It lacks material substance - you can’t touch it or see it.

It is identifiable - it can be identified in order to separate it, sell it, transfer it, licence it, rent it, or exchange it.

It is owned and controlled- an organisation owns it, has the rights to use it, controls it, and is responsible for managing it.

It has probable future economic benefit - data drives value for organisations through its use, for decisions and actions.

Intangibles are a huge part of our economy

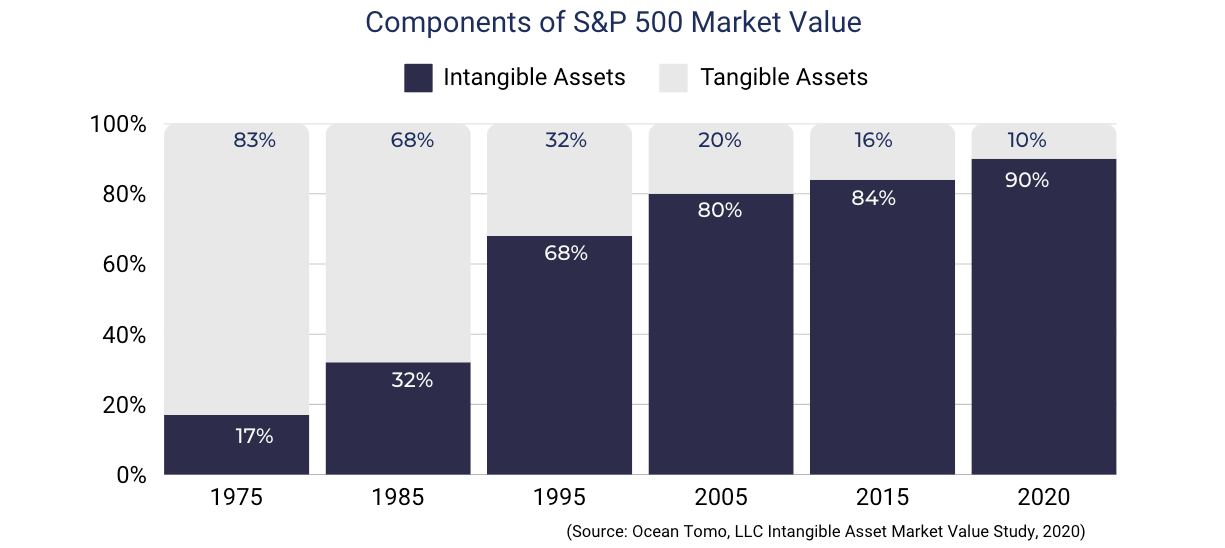

The emergence of digital business models has led to an explosion in the estimated value of intangible assets. Between 2009 and 2019, PWC estimates the implied market value of intangible assets at S&P 500 companies increased 255% while the book value of tangible assets only increased by 97% in the same period.

Because accounting guidance has not recognised the value of all intangibles, including data, much of a company's most important assets are not on the balance sheet. The result can be a large gap between the book value of the company and its market capitalisation.

90% of the S&P 500 market value is composed of intangible assets (IP rights, reputation, and data), according to Ocean Tomo.

If we look at an extreme example, Meta’s market capitalisation was approximately $1trillion in 2021, but the company’s net worth based on balance sheet assets and liabilities was just $138 billion. Much of its value is likely to come from the data it collects from users, which is used to power its advertising business.

There are few useful hard and fast estimates on what proportion of intangibles are made up of data, but I’ve seen estimates in the region of 50% (although this will vary by organisation and industry).

The world’s most valuable companies are ‘data businesses’

In recent years we have seen a significant shift in the basis of company valuation. About 80% of the world’s corporate wealth now resides in just 10% of companies. As the graphic below shows, the shift is striking. Amazon, Alphabet, Visa and Tesla are all new entries in the list of world’s most valuable companies and data is fundamental to their operations.

(These figures are from 2023, and at the time of writing Tesla’s value isn’t quite what it was).

While I don’t like the phrase ‘data is the new oil,’ in this context, it kind of is, with only one petrochemical company still in the top 10.

So, why isn’t data on the balance sheet?

You’d think getting data on to the balance sheet, so it is treated as a formal factor of production, would make a lot of sense. As they say, what gets measured, gets managed.

In some circumstances, data, or at least forms of it has made it to balance sheets - where there is a very clear economic reason for doing so (in other words, it has clear fair market value).

For example, United Airlines and American Airlines secured multi-billion dollar loans collateralising their MileagePlus and AAdvantage customer loyalty programs, based on their customer data assets.

(3rd party appraisals of their customer data suggested that it was worth 2-3 times more than the market value of the companies themselves - let that sink in).

Yet, the guardians of accounting have historically demured from treating data as a capital asset, for a handful of reasons.

Data’s value is dependent on context

Unlike tangible assets (e.g., machinery) or even some intangibles (e.g., patents), data’s worth usually depends on context. Just because data is valuable for one company’s operations, doesn’t mean it is useful for another’s.

The upshot being, it can be difficult to place a fair market value on lots of types of data, which has typically been key criteria for balance sheet inclusion. Indeed, there just isn’t an active market (with reliable pricing) for lots of types of data (albeit some types of consumer and financial data are notable exceptions to this).

Non-separability from operations

Many companies generate and use data internally, and it can be difficult to separate it as a distinct asset with independent value. (Note: despite the challenge, this is actually very possible).

Ambiguous legal ownership

Unlike trademarks or patents, data often lacks exclusive ownership rights. Companies may collect user data, but they don’t always have full legal control over it (e.g., privacy laws like GDPR restrict usage).

Uncertain future benefits

Assets must provide measurable future economic benefits. While data can create value (e.g., improved decision-making), its benefits are often indirect and uncertain (Note: there are also innovative solutions to this challenge).

Accounting is just conservative

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) prioritise reliable, verifiable measurements.

Since data valuation introduces a level of subjectivity, accounting bodies have been hesitant to classify data as a balance sheet asset.

This means data related costs are usually just expensed, rather than capitalised.

(For a good primer on this subject, check out Doug Laney’s infonomics).

As an aside, it is worth noting that as data becomes ever more important to the modern economy, we’re starting to see moves to treat it as a formal intangible asset. In China, organisations can now place data on the balance sheet, and the UN has recently released a handbook on measuring data in the System of National Accounts (while this is at national level, the likelihood is this will encourage industries and organisations to begin the journey to reporting data in their financial accounts).

As a further aside, both approaches value data based on its cost alone, without considering its benefits. This is only half of the value equation - given the cost to acquire, process, and maintain data does not necessarily reflect the value it can create for an organisation.

Data is a special kind of asset

In some ways, the balance sheet debate is a bit of a red herring. Any organisation would do well to understand the value of its data to its operations, irrespective of whether this is formally accounted for.

If you are clear on both the costs and benefits of your data, you’ll be better placed to prioritise investment in data effectively, whether or not it gets on to your balance sheet.

When we consider data as an asset, it is also worth stressing that it has certain characteristics not found in other assets. These influence how it can be used to create value.

Here are 8 laws we can apply to data, derived from the pioneering work of Daniel Moody, on the value of information, which you may want to bear in mind.

It is infinitely shareable

It can be replicated and shared again and again, in theory infinitely, with limited incremental costs.

Many parties can use data at the same time, which is not true of physical assets. This is called non rivalrous, where consumption of a good by one party does not reduce the amount available for others.

Its value can increase with use

The more you use it the more value you can potentially derive from it.

It can be perishable

Data does ‘go off.’ It can have a useful lifetime, and does depreciate like other assets. It will often lose relevance. Customer data sets that are not regularly updated lose their value as over time customers change their contact details, move home, or even die. However its life can be extended or renewed if needed for decision making, so once depreciated data may acquire renewed purpose.

Accuracy & value

The value of information increases with accuracy (go data quality).

Synergies of combined information

The value of information increases when combined with other information. Integration or comparison of information generates additional value. Even a slight standardisation of information can lead to major benefits.

More is not always better

As they say it is what you do with it that matters. Data can have increasing or decreasing returns - collecting more data can lead to more insights. However at other times more data adds little extra value, despite organisations continuing to hoard it.

Data has option value

It is hard to predict how the value of data might change. New technologies (such as AI) may mean existing data has unpredictable future importance. Organisations may keep data for its potential value rather than its current value.

Non-depletable

It is self-generating, the more you use it the more you obtain from it. It can actually generate exponential returns, without being depleted. This is very different from traditional assets that cease to exist the more they are used.

What makes data valuable?

Data’s value is a direct consequence of its use. Value comes from use and use stems from the capacity for data to become usable information. The type of information we can use to make decisions and take actions that matter to us.

The following informational characteristics could all impact the potential usefulness and therefore value of data.

(Check out this paper from The Bennett Institute for a deeper read).

What the data is about: the subjects or events it is about. If we have two data sets and the subjects or events of one data set can help you make a better decision, relative to another, then it is more useful and therefore potentially more valuable.

Its general purpose: it’s flexibility to be used across different types of analysis and ultimately decisions and outcomes/situations.

Its temporal coverage: for example, does it support forecasts, real-time information, historic or backcasts?

Its quality: Its completeness, accuracy, and timeliness, for example.

Its sensitivity: This depends on how you measure sensitivity, however data with a lot of personally identifiable information entails greater cost and risk.

How linkable is the data: This impacts how easy it is to work with and how it can be joined with other data.

Its importance: this is critical, as not all data assets are going to be as important as others. For example if you are an airline, data tracking where your planes are at any given moment is always going to be more important than how many packets of peanuts you have on board.

Every analyst and data scientist worth their salt should be thinking about the informational potential of data. It is something they are trained to do. However, it is worth all decision makers understanding this too, at least at a high level.

What does this mean for managing data?

The fact that not all data is equal (some will just be more useful), underlines the critical importance of data management as it can be deployed to influence the potential value of our data.

In many cases making it more valuable.

Here’s what treating data as an asset means for its management:

You need to identify what is mission critical (in other words, register and define it).

You need to exercise control over it (in other words, make it fit-for-value).

You need to understand its benefit (in other words, value it).

The implication being:

If you don’t identify your data, you can’t manage it, or value it.

If you don’t manage it you won’t know what you have, or be able to value it.

If you don’t value it, there is little point in managing it or identifying it in the first place.

In summary

As ever, I could go on. But this is a 101 and I’ve at least introduced the basics.

Whether or not we see data on the balance sheet (it does seem like we’re getting closer), data meets the intangible asset test, and organisations that treat it as such will always be better placed to maximise it for competitve advantage.

As far as I’m concerned, an asset mindset is the secret to great data management.